Michelle Alexander on Reclaiming the Body Through Art

Michelle Alexander, Split Self, 2021, digital image on paper

Chicago-based artist Michelle Alexander is not afraid to make you uncomfortable—especially if you’re standing on her nipple. In this conversation, Alexander and I discuss everything from her recent exhibition My Body/Your Object, which featured carpet-sized images of her skin that viewers could walk on, to how her fashion background helped shape her craft now. Whether talking about curating shows or the highly personal works of Félix González-Torres, Alexander’s interest in the body—as something consumable, shared between people, soft yet unruly—leaks into every word. There's no shortage of artists' work about the body, but, given that our animal selves are the source of all experience, the body—as Alexander proves—will never be dull material.

— Mieke Marple

Mieke Marple: In your most recent exhibition My Body/Your Object at Mathew Heberlein Contemporary, you printed out oversized close-ups of your body that visitors could walk on. These close-ups feature skin folds, cropped nipples, and freckles. What was your intention here?

Michelle Alexander: I was trying to create a physical confrontation between the viewer and my body, but not in a voyeuristic way. These images are intimate but not flattering. They’re cropped, zoomed in, and raw. I wanted to remove the typical cues we use to categorize bodies, especially female bodies, and instead show skin as terrain, as surface. Letting people walk on these images raised questions for me about ownership, consumption, power, and awareness. It was less about making a statement and more about offering a moment of discomfort or pause.

Michelle Alexander, Grounding Touch, 2021, digital image on paper and lino print on mylar

MM: Did the way visitors interact with the works surprise you? Were there any differences between what you expected and what actually happened?

MA: Definitely. Some people walked right across the carpets without a second thought. Others hesitated and walked around, or asked if it was okay. That hesitation said a lot to me. Watching people decide how to move through the space revealed something I didn’t fully anticipate: my own dynamic with people-pleasing. It made me wonder if putting myself literally on the floor to be walked on was a way of reclaiming that tendency, of setting new terms for how my body is engaged with. The work became a kind of boundary-setting exercise, even as it appeared boundary-less.

I was also hyper-aware of if and when people even realized they were interacting with the works; drinking it, eating it, holding it, stepping on it. That blur between art and environment was intentional, but it also left me wondering: When does the work become more about them than me? Or is that transfer even possible? I don’t think I have a clear answer yet, but that tension between control and release, between author and audience, has stayed with me.

Michelle Alexander, "My Body/Your Object," 2025, installation view at Mathew Heberlein Contemporary, Chicago IL. Photo credit: Jonas Muller-Ahlheim

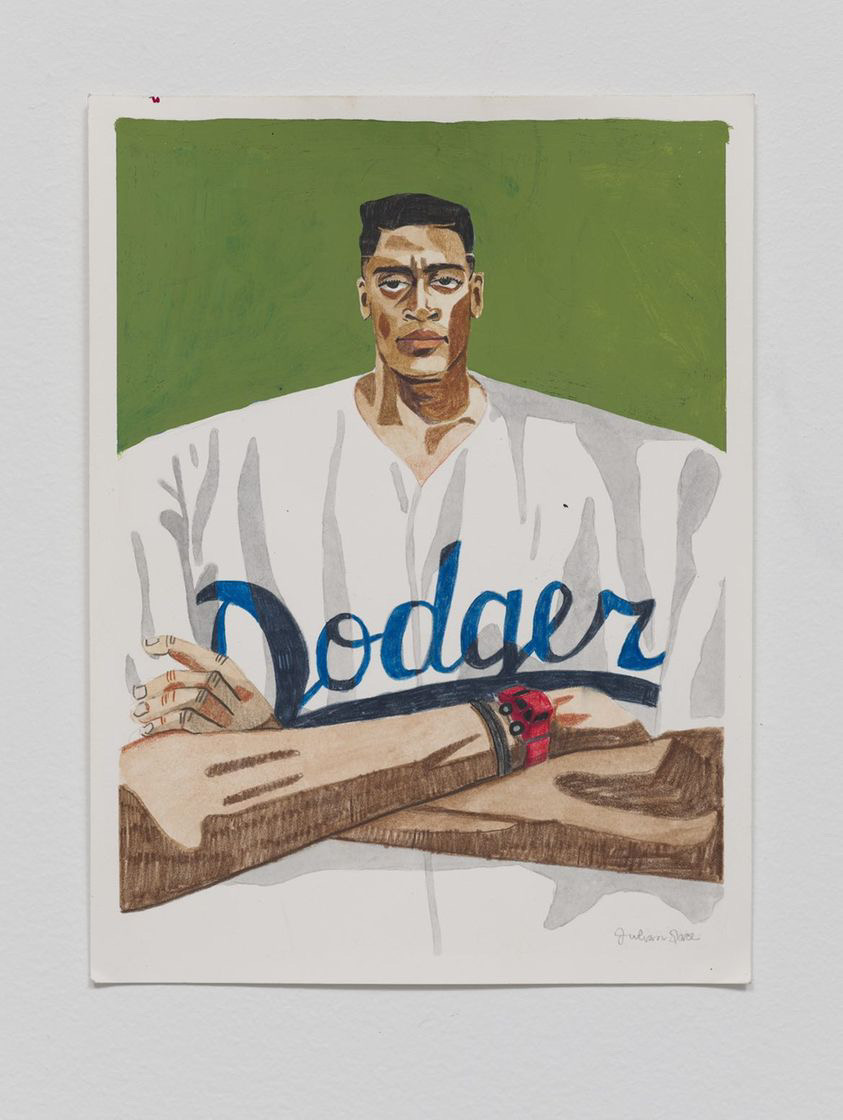

MM: I see echoes of Eleanor Antin’s “carving piece” and Marina Abramović's “Rhythm 0” in this piece. What is the artistic legacy that you see yourself a part of?

MA: Wow, that is so flattering to be talked about in conversation with those incredible artists and those works that feel both surreal and deeply meaningful. I definitely look to artists who use their bodies as material, especially women who use their bodies as a canvas in ways that are surprising, uncomfortable, and complicated. That legacy matters to me not in terms of notoriety or performance, but in how those artists create space for bodies that don’t behave or perform in socially acceptable ways. My work is part of that lineage, but it’s also grounded in installation and material manipulation. I’m interested in what the body leaves behind: impressions, fragments, traces. It’s less about performing the body in real time and more about making its presence felt after the fact, what lingers, what’s carried, what’s been touched, changed, or awakened inside you.

MM: You worked as an associate designer at Amur, assistant designer at ML Monique Lhuillier, and an assistant designer at Longstreet, developing garment designs for brands like US Polo Association, Limited Too, Kensie Girl, New Balance Girls, and Nine Threads. How does your background in fashion inform your art practice? Were you always making art or is artmaking something you came to later?

MA: Art and creative expression have always been central to my life. Before studying fashion, I studied painting and photography in undergrad. Making art has always been my best outlet for trying to understand myself and the world around me.

Fashion came later and became my first real education in how bodies are controlled. I learned how silhouettes can be shaped, how garments can seduce or restrict. That had a huge impact on how I think about form. In my artwork now, I still use fabric, structure, and decoration, but I twist them. I make them heavy, raw, awkward, and vulnerable. My relationship to fashion and my body is complicated, and that complexity drives a lot of my practice.

The pressure to be thin, beautiful, put together, or perfect trickles into every part of the fashion machine. That pressure is palpable, and it stays with you. It gets under your skin, into your daily habits, and shapes your sense of self-worth.

While I was always creative, I didn’t come into art seriously until later. It became a way to process everything left behind in me. Through my work, I’m often trying to reclaim the body, to disrupt those systems of control, and to ask new questions about how we define beauty, power, and presence.

portrait of Michelle Alexander

MM: You also recently curated a show “Connective Thread” at Ivory Gate Gallery that included work by Michelle Grabner, Adrianne Rubenstein, and yourself, among others. What made you want to curate this show, and how do you see curating as an extension of your practice?

MA: That show came out of admiration and creating opportunity, honestly. I was a fan of these artists first. I reached out to people I deeply respect, and I was lucky they trusted me enough to say yes. The show was rooted in my own questions about womanhood, softness, and strength. I was looking for work that engaged with the body not just as subject, but as material, as something to be shaped, tested, and transformed.

Curating gave me the chance to create a space where different forms of embodiment could be in conversation. It felt like assembling a shared nervous system. The decisions I made were intuitive and personal, completely tied to my own practice. It didn’t feel like a separate role; it felt like an extension of the same questions I ask in my studio.

So much of the time, how and where artists show their work is taken out of our hands. Curating felt like a way to reclaim some of that. To mold the vision, shape the atmosphere, and build a context with intention and make it happen. It gave me the opportunity to expose myself and others to artists I admire and to bring that admiration into a public, collective space.

MM: What are you working on now? And where do you see your work going in the next five years?

MA: I’m working on some new sculptural installation pieces that explore how the body responds to external pressure, especially within male-dominated spaces. I’m experimenting with fragmented forms and possibly integrating sound elements to deepen the physical and emotional impact. I’m still really interested in how environments can hold the weight of a body or push against it and how materials can carry emotional residue.

A lot of my focus continues to be on the complications of being in a body, trying to understand it, and building spaces where viewers can see themselves and feel seen. I want the work to create moments of confrontation but also recognition, especially around the layered and often contradictory experience of being in a female body.

Looking ahead, I hope to push further into immersive installation and maybe start working in more public or site-responsive contexts. I want to continue using materiality to shift emotional landscapes, not just visual ones.

In five years, I hope I’m still making work that is honest, uncomfortable, and generous in its tension, work that opens space for softness, contradiction, and deeper understanding of embodiment, especially within the ongoing messiness of just being.

Michelle Alexander, Flayed, 2022, digital images on organza, charcoal, pins, dressforms

MM: If you could ask a question to any artist, living or dead, who would you choose and what would your question be?

MA: I’d like to talk to Félix González-Torres. I’d ask him how it feels to see people interact with “Untitled” (Portrait of Ross in L.A.), to watch them take candy, eat it, and walk away. How does it feel to see something so heavy handled through sweetness? What does it mean to make grief consumable, to represent a body as a pile of shimmering candy? I’d want to know what candy meant to him in that context, what the sugar, the metallic foil, the act of giving away and disappearing stood for emotionally, politically, personally.

I’d also ask about the role of the viewer, how it feels to have them physically participate in the piece, to complete it, even when they might not fully understand what it’s about. When the work is so deeply personal, how does it feel to have that meaning fragmented by the public? Does it matter if they don’t know the story? Or is that distance part of it, too? I think his ability to hold intimacy and anonymity in the same gesture is incredibly powerful, and I wonder how he carried that tension as an artist and as a person.

To learn more about Michelle, follow her Instagram and visit her website.

Michelle Alexander, Weight of the Ideal, 2024, mixed media

Michelle Alexander, The Pressure, 2025, installation view at Ivory Gate Gallery, Chicago IL.

Michelle Alexander, Pieced Back Together, 2021, mixed media

For more from Mieke:

Miekemarple.com

Instagram

Substack

You must be logged in to post a comment.